When you dream at night, are the stories you encounter a product of your individual mind or something more communal? Robert Campany, a historian of medieval Chinese religion, says that how you answer that question depends in part on when (and where) you were born.

“Modern views of dreaming generally start with the assumption that dreams are made by the dreamer and are fundamentally about the dreamer,” he notes. “In medieval Chinese thought, however, dreams are not made by the dreaming self but are rather shown to or emplaced in it by other agents; and dreams mostly do not concern oneself or one's past at all. The personal is mere signal interference.”

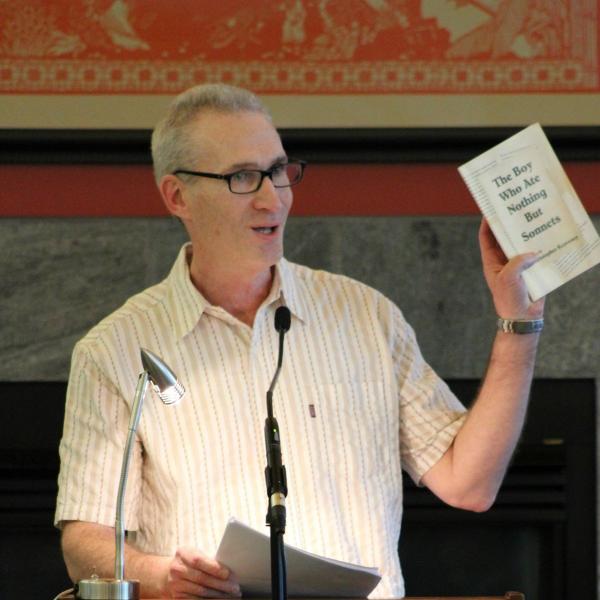

On November 2, Campany will deliver the second annual Robert Morrell Lecture in Asian Religions on the subject of “Dreaming Religious Identity: Master Zhou's Communications with the Unseen World.” A specialist in comparative Chinese religious history from 300 BCE to 600 CE, Campany is currently writing a book about what he terms the Chinese dreamscape – the surprisingly flexible and pan-religious set of beliefs surrounding dreaming in medieval China.

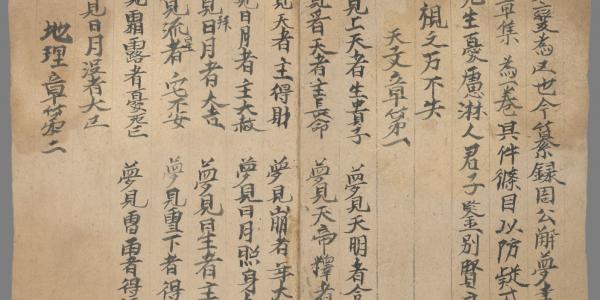

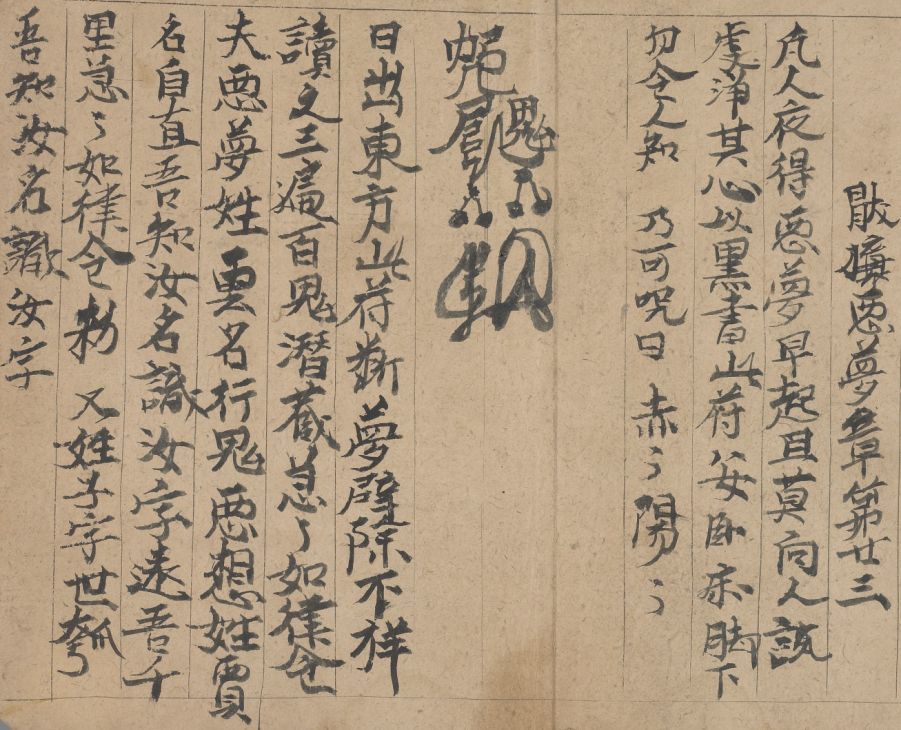

By touching on a wide range of “dream texts” – including poems, interpretation manuals, and texts describing dream rituals – Campany’s work reconstructs a literary culture of dreaming. What emerges, he notes, is a surprisingly flexible landscape where what dreams mean and even what dreams are is more open to interpretation than might be expected.

“One of the things I argue in the book I am writing,” he says, “is that what I term the ‘dreamscape’ of ancient and medieval China had a certain structure to it, a structure that can be mapped. And that structure doesn't correspond to the usual ‘isms’ into which we customarily divide Chinese religious and intellectual history (Daoism, Buddhism, Confucianism, etc.), nor does it change significantly over time.”

In medieval China, he explains, dreams were often understood through mapping, “by bringing them into some sort of order, fixing them into grids, and reading them as signs from a chartable cosmos.” While others saw dreams as “flying free of all maps, signifying nothing but the folly of map-making,” the idea of a dreamscape remains a defining conceptual framework for Chinese writings about dreams.

You can learn more about the cartographic imagination of Chinese dreaming on November 2 from 4 -5 pm in the Women’s Building Formal Lounge. For more information about the event visit the East Asian Languages and Cultures website.

The Robert Morrell Lecture in Asian Religions commemorates the work of Morrell, a specialist in Japanese literature and Buddhism who taught at Washington University for 34 years. It is co-organized by East Asian Languages and Cultures and by Religious Studies.