With the recent launch of our new major in Korean language and culture in 2016, we wanted to celebrate the accomplished history of Korean language study at Washington University by profiling a number of our alumni who have gone on to win Fulbright fellowships to study in South Korea. From teaching English to pursuing graduate work in Korean studies, our alumni have done amazing things both abroad and at home. We’re thrilled to be able to collect some of their stories here.

Spirit of Korea

Ezine Arizor (’16) received a Fulbright U.S. Student scholarship in 2016 to pursue a master’s degree in Korean Studies at Yonsei University in Seoul. Her first introduction to Korean culture came in the form of the Korean television dramas Arizor watched in high school, but it was becoming friends with Korean international students on WashU’s campus as a first-year student that drew Arizor to studying the language and culture of Korea. “My interest grew after watching WashU's Korean cultural festival, Spirit of Korea, during my freshman year,” she reflects, “and from then, I was encouraged by Korean language Professor Mijeong Kim and Korean literature Professor Ji Eun Lee.”

During her Fulbright fellowship, Arizor studied media, history, society, language, and popular culture. Taking advantage of independent studies with faculty on subjects like the impact of immigrant and minority groups on Korean national identity, she has focused on the tension created by the legacy of fierce national identity in an increasingly diverse society. These initial explorations led to her master’s thesis on the portrayal of biracial Korean children in the media.

The opportunity to do cultural studies work in Korea has made Arizor even more aware of the language’s expressive range. “I learned how important and difficult communication is through learning the Korean language,” she says, noting that “Korean is an expressive language and it has taught me different ways to show my feelings and share my thoughts.”

As her time at Yonsei draws to a close, Arizor is looking for ways to use what she learned there in her career, hoping to take the Test of Proficiency in Korean (TOPIK) and use her Korean language skills in whatever challenge she sets for herself next.

From a Cheoan classroom to a New York law firm

Carolyn Carpenter (‘13) received a Fulbright English Teaching Assistant (ETA) fellowship in 2013. For two years Carpenter taught English at a local high school in Cheonan and at a school for North Korean defectors, and worked with other ETAs and the U.S. Embassy to put on conferences for her students. Though she has since moved from teaching to the law, she still returns to the lessons she learned on both sides of the teacher’s desk.

Gaining proficiency in a new language was one of Carpenter’s goals as a new college student. A political science and international and area studies major, she was fascinated by the political situation in Korea. She soon discovered that the language was equally fascinating. “Korean is at its core incredibly logical but still challenging because of its complexity,” she notes. She found that “studying Korean is engaging because the more you learn the more things you already learned makes sense and the more you can develop an intuition to understand even things you haven’t formally learned yet.”

That love of the complexity of the language proved useful in her Cheonan classroom. She still keeps in touch with many of her students, some of whom are now college students themselves. “They have never ceased to make me laugh, inspire me, and encourage me to grow,” she says, adding that “Cheonan literally means comfortable place under heaven and thanks to them that is how I will always feel about Cheonan.”

Carpenter graduated with a JD from the University of Pennsylvania law school in May and is starting a job as an associate at a law firm in New York in the fall. Though working as a lawyer in New York may seem far removed from teaching English in South Korea, she has found her language and translation training to be indispensable. “Law school tends to emphasize the importance of rationality and logic,” she observes, while “in Korea, in order to do my job effectively, I regularly needed to rely on the ability to both speak as simply as possible and build rapport with those around me despite language and cultural barriers. As I prepare to start my legal career, I still see the importance of both removing unnecessary complexities and not losing sight of the shared humanity in all of my professional relationships.”

Returning home

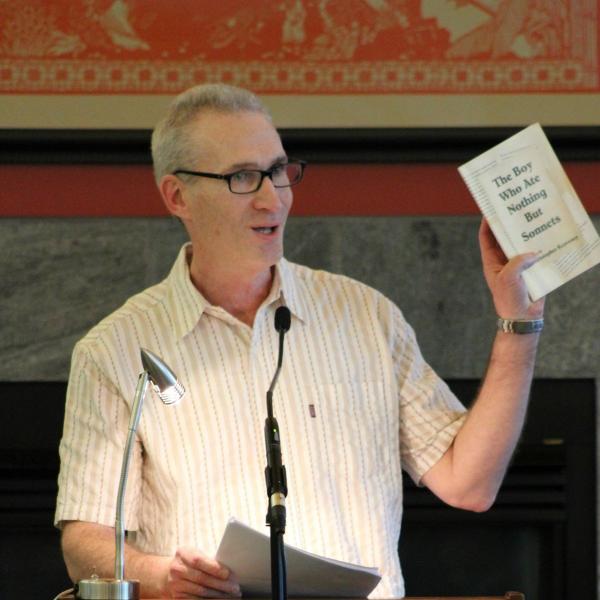

After a turn as a Fulbright Fellow in Korea, Daniel Pieper ('11) pursued an MA degree in East Asian studies from WashU, graduating in 2011. Dr. Pieper later returned to WashU as the Korea Foundation Postdoctoral Fellow, with a PhD from the University of British Columbia in hand.

His research and teaching explores how Korea sought modernization through the transformation of its written language, literature, and education system in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. He talks about the language with the facility of a linguist, fascinated by the evolution of things like orthography and syntax. His initial interest in the language, however, was more pragmatic. Working as an English teacher in Korea, he first learned the language in order to be able to live more easily in South Korea. “What initially was a one-year appointment eventually stretched to six,” he says, “and I enrolled in every Korean language course that I could possibly find. Not only did it enhance my own daily experiences and facilitate many friendships, but I became fascinated with the mechanics of the language itself.”

He went to Korea as an English teacher, but soon became a student himself, excited by the chance to be fully-immersed in a foreign language and culture. He notes that spending a year in a foreign country “can be a life-changing experience, especially for undeclared students who are still contemplating what to study. This can also make a huge impact on language proficiency. From my own experience, one year of immersion education can easily equal three to four years of classroom education. Even if you decide not to major in East Asian languages and cultures, studying abroad offers a host of opportunities for networking and personal growth. Proficiency in a foreign language is also a skill that is useful in a variety of occupations, and helps the learner view the world from a different perspective.”