This National Poetry Month, two faculty members discuss the enduring value of sound when learning poetry in languages that no longer have native speakers.

From printed odes to slam performances, poetry can take many forms. The balance between speaking, hearing, and reading is the foundation of how poems make meaning. Helping students to access that meaning is difficult enough with poems written in their native tongue. It is even more challenging when the students are trying to make sense of a poem that they only interact with on the page.

When ancient Roman poets wrote in Latin, their language was not just the language of poetry. It was the language of commerce, the law, science, and mundane tasks. Students reading those poems today lack immersion in this everyday sense of the language. Cathy Keane, professor and chair of classics at Washington University, encourages her students to cultivate a relationship with poems as heard objects. Reconstructing the sound of a poem within the larger context of a language is an essential task of a teacher of ancient poems, says Keane.

“Poets wrote their work to be heard as much as read, and many, such as early Greek poets and dramatists, wrote verse solely for oral performance,” explained Keane. “We understand a poem better when we hear it and speak it. Just as we get more out of reading poetry in its original language, so too we get more out of hearing it out loud and even forming it with our mouths and voices.”

“Poets wrote their work to be heard as much as read, and many, such as early Greek poets and dramatists, wrote verse solely for oral performance.”

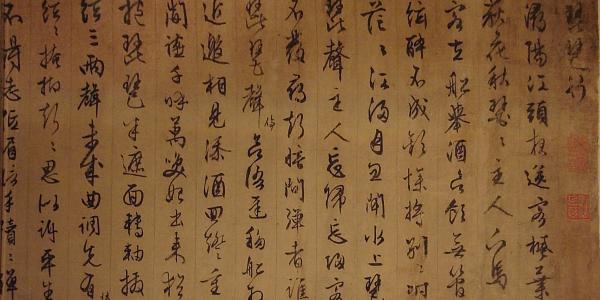

Reading poems aloud in the original language opens up meanings that otherwise may be lost in translation. Jamie Newhard, associate professor of Japanese language and literature, notes that wordplay is particularly difficult to translate. The joy and surprise of hearing two meanings at once is often dropped when a poem is translated.

“What can be challenging to convey in translations of classical Japanese poetry,” Newhard said, “is a sense of the sometimes very intense wordplay that is going on in the brief scope of the originals and that just can’t be rendered in translation, such as the use of a pun-like device called a ‘pivot word’ that allows the same word to convey two different meanings simultaneously.”

In some instances, accessing those sounds is relatively easy for modern readers. Newhard notes that romanized Japanese is relatively straightforward for English speakers to pronounce. The grammar, however, is more difficult to follow. “In a classical language class,” she said, “unpacking all the wordplay that poets managed to cram into 31 syllables and the flow or logic of a poem as it unfolds from beginning to end is challenging, but fun.”

Teaching students to hear classical poetry begins with retraining the way that they approach written texts. Poems make up a significant portion of the remaining texts in ancient languages, so students often begin studying languages like Latin by reading poetry. If a student first encounters Virgil as an exercise in learning grammar, they have to learn also how to see — and hear — his work as poetry.

“There’s a reason why ancient Roman schoolteachers had children learning poetry from an early age and returning again and again to poems like the Aeneid,” said Keane. “But it’s also true that by studying poetry ‘for the Latin,’ students can understandably forget to think of it as poetry and to enjoy all its dimensions. It is really important to devote time to reading out loud, listening, and discussing sound effects, word-arrangement, and style.”

Adjusting to seeing a visual artifact of an ancient culture as something to be heard as well as seen can be difficult. But learning to hear while reading, Keane says, is one of the most rewarding aspects of studying poetry written thousands of years ago.

“Many students can be shy about turning their usually very visual, page-oriented study of this language into an experience of speaking and listening,” said Keane. “I certainly was, and I still enjoy the relationship with the silent page. But it’s also fun to read out loud. It’s important to remember that sometimes you can only decipher meaning by paying close attention to sound or composition.”

In this video, Cathy Keane reads from “On the Nature of Things,” a poem by Lucretius that she regularly teaches in her classes.

Here Jamie Newhard reads two short poems written in classical Japanese.