Rebecca Copeland is professor of Japanese language and literature and co-editor of “Yamamba: In Search of the Japanese Mountain Witch.”

Deep in the Japanese mountains where the cryptomeria are thick and time is forgotten, you may encounter a woman. She lives alone in a modest hut spinning thread. Content to watch the wheel turn round and round, to let the moon and sun spin past, she asks for nothing and bothers no one. But every now and then, as night falls, a man will stumble along her path, or sometimes two men, or an entire retinue of traveling priests, and they will beg her to take them in for the night. Perhaps they lost their way, or maybe they misjudged the speed of the sun’s descent and found the woods growing darker than expected. She declines their request at first. Her hut is small and hardly fit for men as fine as these, dressed in palace vestments or temple finery. She is poor. Besides, she thinks but doesn’t say, why should I be responsible for their inability to read a map or tell time. Still, the men persist, and she takes pity on them.

“Don’t open the door to the inner room,” she warns as she heads out into the woods to collect kindling. She’ll need to feed the fools.

So what do you think they do the minute she is out of sight?

You already know.

They poke their noses right where she told them not to. And when they do they discover to their horror that her inner room, her forbidden chamber, is full of the corpses and bones of all the men who came before them.

The woman is a yamamba, or Japan’s mountain witch.

Before she even returns to her hut, she feels the sharp scrape of the men’s scrutiny. She sees herself now through their eyes. She is not a kindly old woman living alone spinning thread. She is a monster.

She chases the men, her horns in full view, her fangs gleaming.

They get away. They have to. Someone has to tell the story. They get away by reciting sutras and relying on the benevolent power of the Buddha to protect them.

And she is forced to burrow deeper and deeper into the mountain fastness.

Wherever a woman lives alone; whenever she steps beyond the polite expectations of the village, the temple, the family, the rules and order, she eventually reveals her yamamba horns. It is inevitable.

In ancient times, a woman alone was a woman doomed. Isolated, at the mercy of other sojourners for sustenance and protection, few women — or even men — could survive beyond the sheltering folds of the community. Those who did, therefore, had to be extraordinary, barely human, if at all.

The legend of the yamamba has been passed down from the medieval era to the present. She has appeared in poetry, prints and theater and has served as both cautionary tale and entertainment. In the late 20th century, women writers began a reassessment of the yamamba, finding in her glimmers of themselves. What led the yamamba to the mountains? What made her solitary existence so threatening to patriarchal power structures? As artists many of these women put their own creative vision above the demands of their families, laboring long into the night, leaving for artist retreats, forgetting to brush their hair. Rather than an emblem of fear or even pity, the yamamba represented freedom for these artists, a way out of the pressures of social propriety, an opportunity to let their creative spirits roam the mountainsides. But the yamamba also embodied vulnerability. Exposed to the censorial gaze of society, she (and these artists) were susceptible to scorn. More importantly, they were susceptible to loneliness. Freedom comes with a price.

At the end of the 20th century in Japan, there was a movement among a small but daring group of girls on the cusp of womanhood. They tanned their skins, bleached their hair a platinum blonde or silver, and circled their eyes and lips with white makeup. Their appearance was so caustic to conservative adults — those roving priests of propriety — that the girls were dubbed “yamamba.” The label was meant to shame them, to push them back into their rooms overstuffed with electronics and Hello Kitty pillows. But these young women, like their namesake, refused to obey. They owned their title. Referring to themselves as “Mambas,” they paraded proudly along city streets.

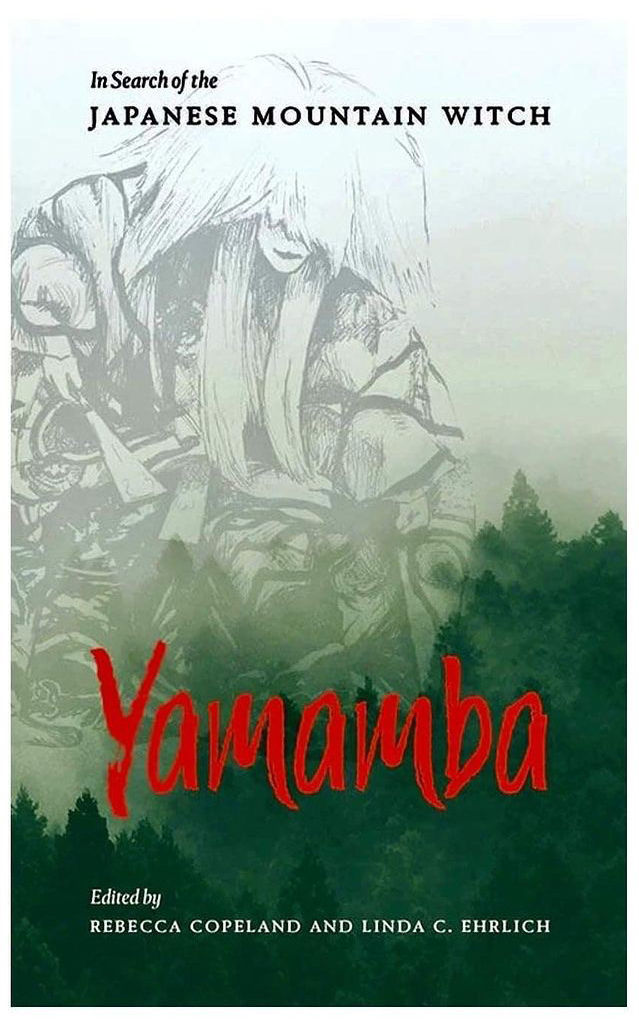

Never one to be contained, the yamamba has crossed the ocean. Now and then I’ll find her racing ahead of me on a wooded path in the Blue Ridge Mountains or starring back at me from the corner of my bathroom mirror in University City. She’s fearless and almost always laughing. Not that big bellied “ha-ha” kind of laugh but the kind that winks from the corner of her eyes. She has power. Out of nowhere, it seems, she inspired Linda Ehrlich and me to collaborate on a book about her. Yamamba: In Search of the Japanese Mountain Witch, published in June by Stonebridge Press, showcases the variety of ways the yamamba has empowered art, be it dance, poetry or painting.

“What’s with the title?” she asked me once. “In search of? I’m right here.”

And she is. But she is also always somehow just out of reach.

Headline image: The mountains of Shirakawa, Japan by Laura Thonne via Unsplash